Writing Code Without Plain Text Files

The Unison programming language doesn't store code in files, but in a database. What is that like?

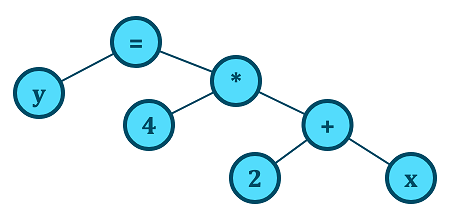

For about a week, I have had the unusual experience of writing code without the usual hierarchy of folders and plain text files that us programmers are accustomed to. Instead, my code has been living inside an SQLite database, stored as abstract syntax trees (ASTs). If you don't know what an AST is, allow me to clarify. Consider a simple statement in a programming language such as:

y = 4 * (2 + x)When you compile or interpret that statement, it will first be turned into tokens by a lexer which pass those tokens to a parser which tries to figure out the grammatical structure of the statement. The parser will produce an abstract syntax tree (AST) representing that statement. An AST is a tree-based data structure. The illustration below helps give you an idea.

Anything in source code can be represented as an AST. A function definition or a type definition will get parsed and turned into an AST. Depending on the language, this AST is also what is used to execute statements in the program or to produce the machine code that will get executed.

The particular programming language I have used, that chooses to store code in its compiled form, is called Unison. It is a pure statically typed programming language which might look familiar to anyone who has ever toyed with Haskell or another ML-like language such as OCaml, Standard ML or F#.

I am actually not particularly interested in that kind of language, being primarily a big fan of dynamically typed languages such as Julia and Lua. Yet for the last week I deliberately went ahead to learn Unison, despite not being particularly interested in it. So, why did I do that, and what was my experience?

The reason was specifically because I wanted to find out what non-file-based programming is like in 2023. It is not an entirely new concept. For instance, the Smalltalk programming language which dates back to the 1970s eschews file-based development as well. I write more about the implications of such a choice in modern Smalltalk in the following article:

Unison, however, is the first time I have seen a serious attempt at radically evolving this concept. Unison is mixing ideas from Smalltalk, Haskell, REPL-based development and the Git version control system into something entirely new.

If Git was an IDE

With the Git version control system, you check files in and out of what can be viewed as a database or content addressable file system. Git tracks changes over time and allow you to do things such as undo previous changes and track and compare changes.

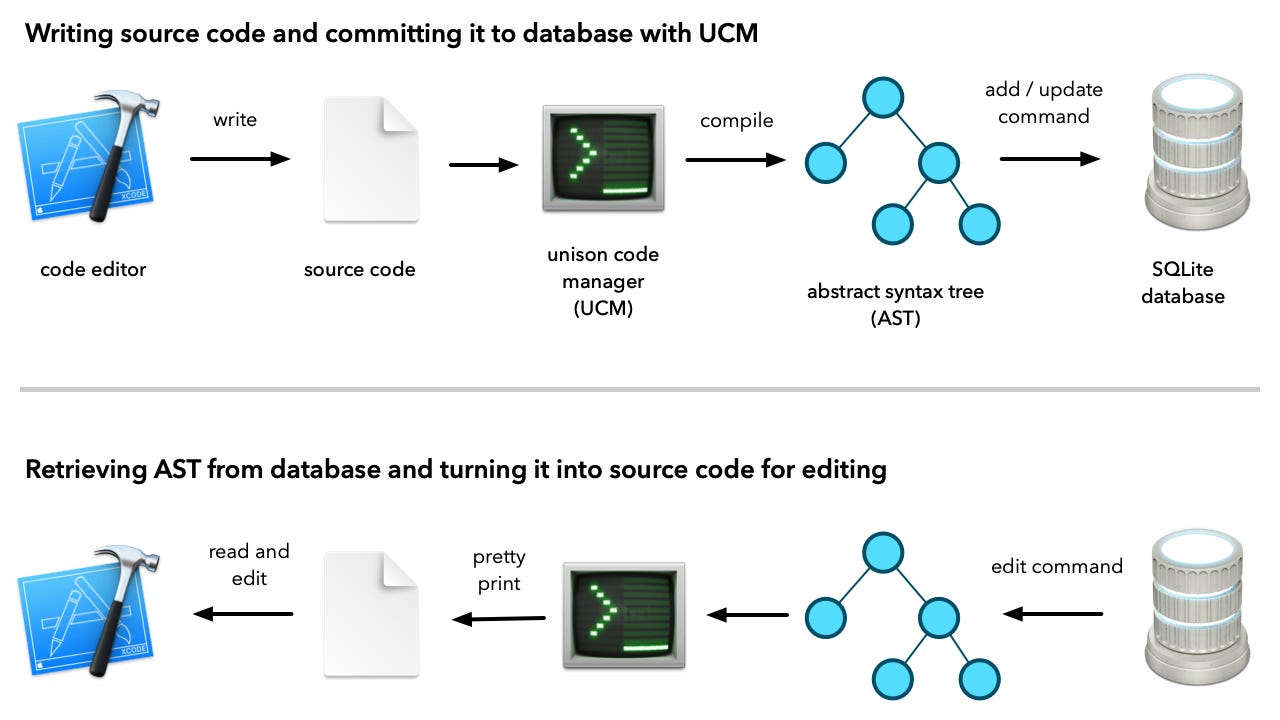

You can think of Unison as working much the same way, but at the level of individual functions and type definitions. When you work on a project managed by Git, it will tell you which files have been modified and give you the option to commit those changes. While working with Unison, you run a sort of shell called UCM (Unison Code Manager) which monitors changes.

Rather than telling you which files you have modified, it will inform you of which functions have been modified or added. By typing the command add at the UCM prompt you commit those changes to the Unison code database, which typically lives in a subdirectory called .unison under your home directory .

All the changes you commit to the Unison code database creates a history. You can later look at your history and perform diffs. You can even undo specific changes.

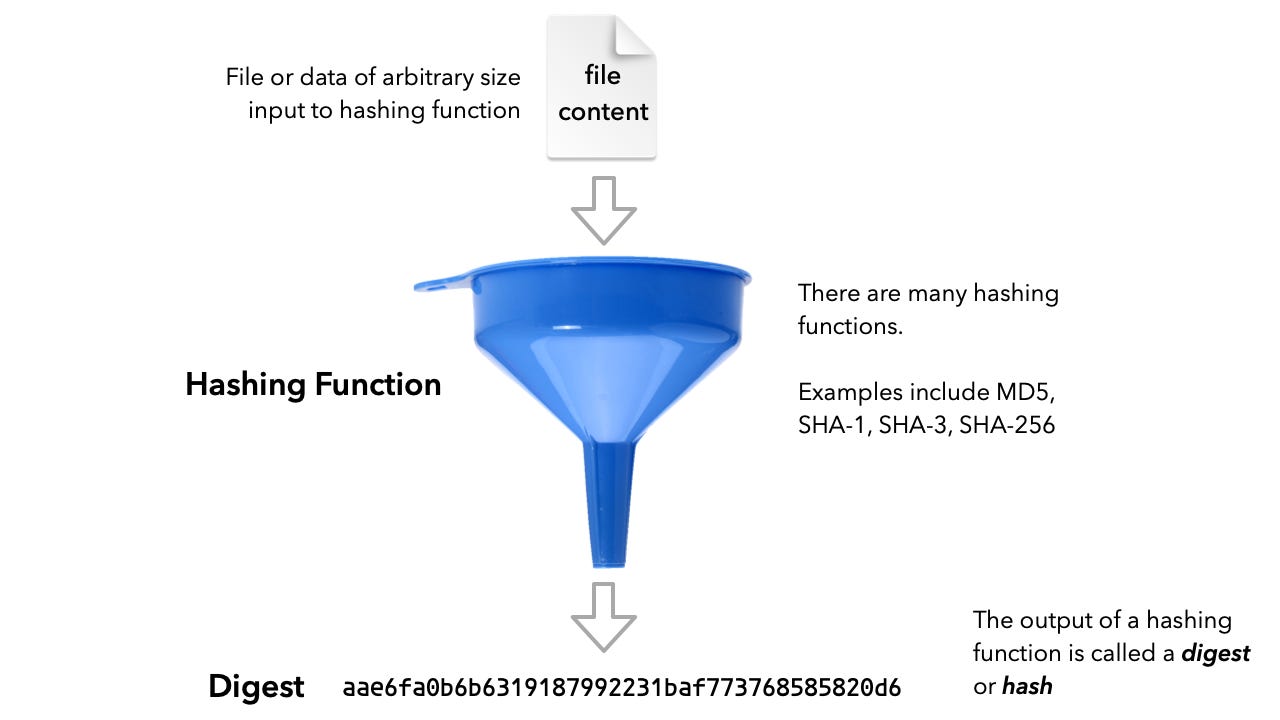

Unison copies several other important concepts from Git. Most significant is the idea of content addressable objects. This concept is related to hash functions.

A hash function will take any data, say a file, of arbitrary size to calculate a unique number called the digest or hash based on the content. Regardless of the size of the input data, the digest that pops out is always of the same length. Git uses the SHA1 hash function to produce a digests of 120 bits (20 bytes). In principle two different files could end up with the same hash, but the probability of that is miniscule. It has been compared to picking two random locations on the Earth and picking up the same grain of sand. Unison uses SHA3 to produce a digest of 512 bits.

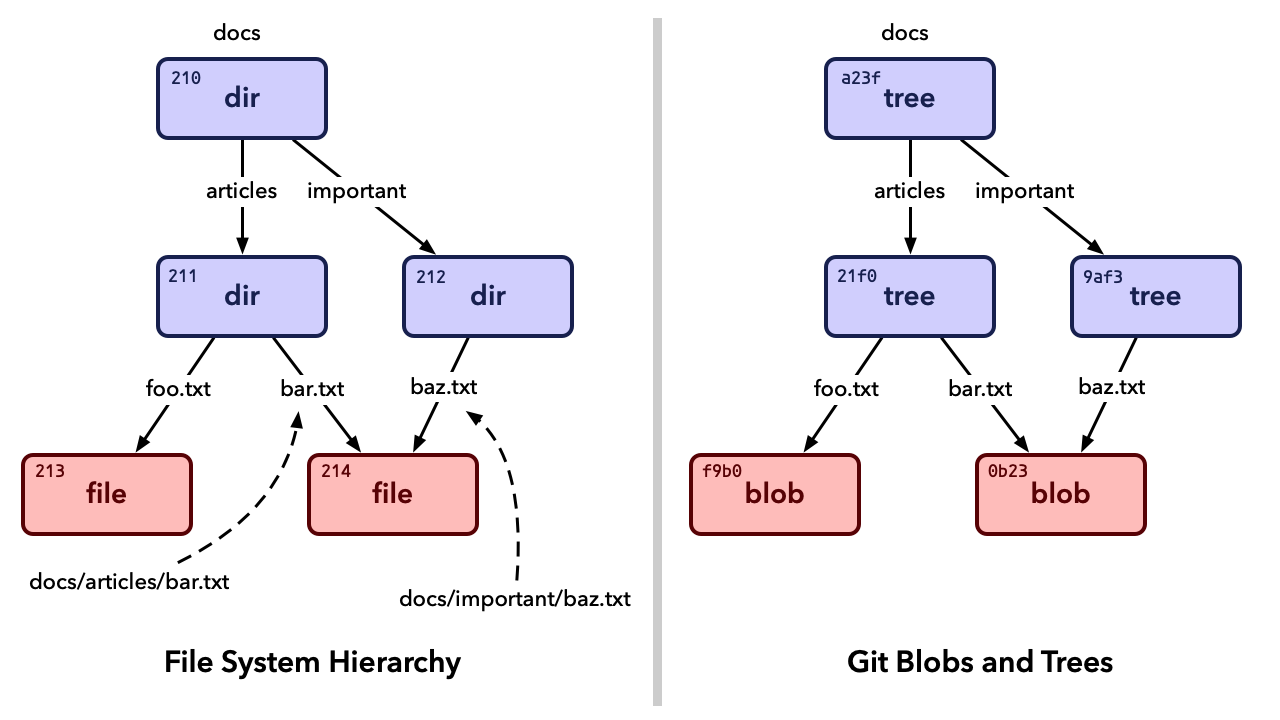

Both Git and Unison uses hashes to uniquely name and identity data. To explain how this works in Git, I like to contrast how Git stores tree and blob objects with how a Unix file system stores directories and files.

In Unix, every file and directory is uniquely identified with an inodenumber. In my illustration above they are the numbers 210, 211, …, 214. Of course, in a real system, the inode numbers would be much bigger.

The name of a file and its path is independent of its inode number. For instance, the same file can be accessed through different file paths. In my example docs/articles/bar.txt and docs/important/baz.txt refers to exactly the same file.

Inode numbers differs from hashes, which are used to identify tree and blob objects in Git in that they are not related to the content of the file. A file can change content while keeping the same inode number. For Git in contrast, if you change the content of a blob, it gets a different name. In other words, objects which have the same content always have the same name while objects which have different content have different names.

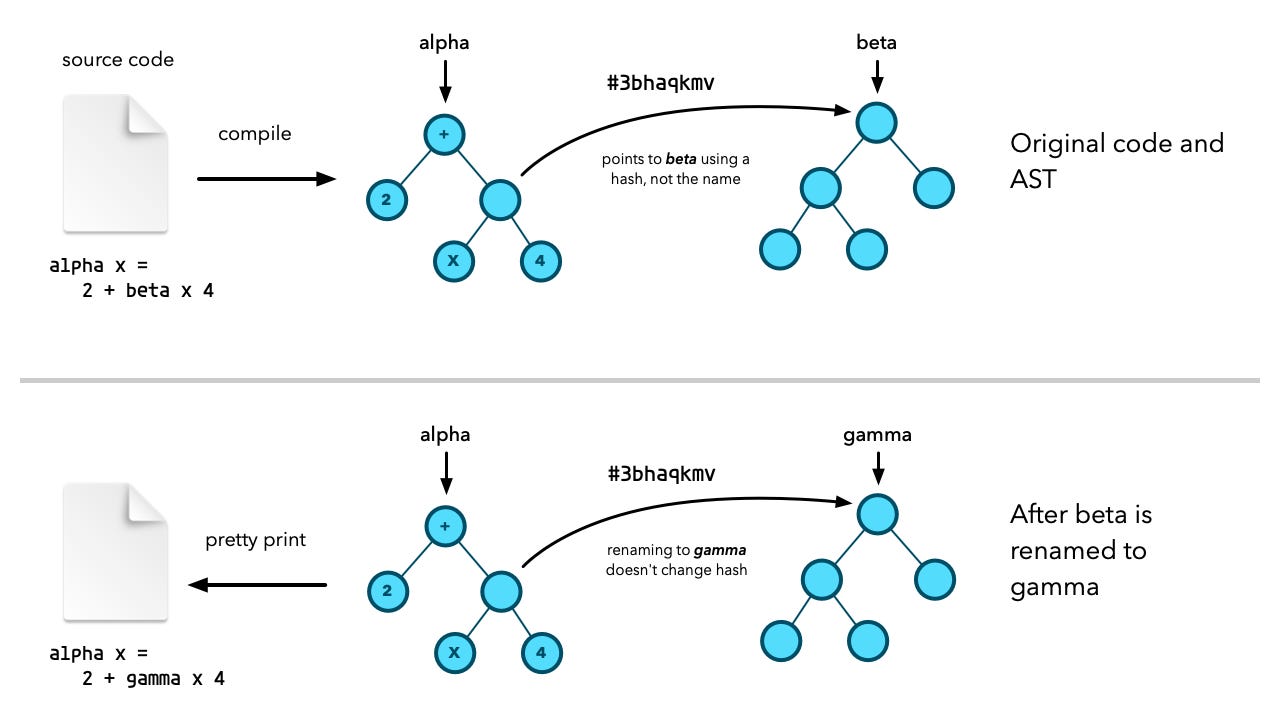

When you commit a file to Git, it will run it through a SHA-1 hash function to produce a SHA-1 digest (hash). The file then gets stored with that SHA-1 digest as its name. The same thing happens when you commit a Unison function to its database, with a couple of important differences: Unison does not commit the source code of the function. Instead, Unison produce an AST of the code. When creating this AST, Unison will look up the digest (hash) for each function, variable or type you use. The hash is the actual true name of the functions your code calls. The names you use when editing code are just aliases or pointers to those hashes.

An AST with hashes referencing other functions is what is pushed through the SHA3 hash function to produce a 512-bit digest that uniquely identifies the function you just committed.

Implications of Using Hashes To Identify Functions and Types

Say you write a function alpha which references a function beta you previously committed. It doesn't matter if you should later change the name of beta to gamma. The AST for alpha which you stored references beta by hash and not name. That means renaming beta to gammadoesn't invalidate that reference. You can even move beta to an entirely different namespace (package for Java developers) and it has no consequence. Your code will still run just fine. Nothing breaks.

In fact, the implications are even more profound. You can transmit the AST of a function to an entirely different computer. Locally, that computer can determine if it has all the required functions. Functions with the same code will give the same hash regardless of what computer you calculate the hash on. UCM on the remote computer can thus quickly determine whether all dependencies are satisfied and explicitly request only the dependent functions from the sender.

What that means is very fine-grained control when distributing code.

How Do You Fix a Bug in a Unison Function?

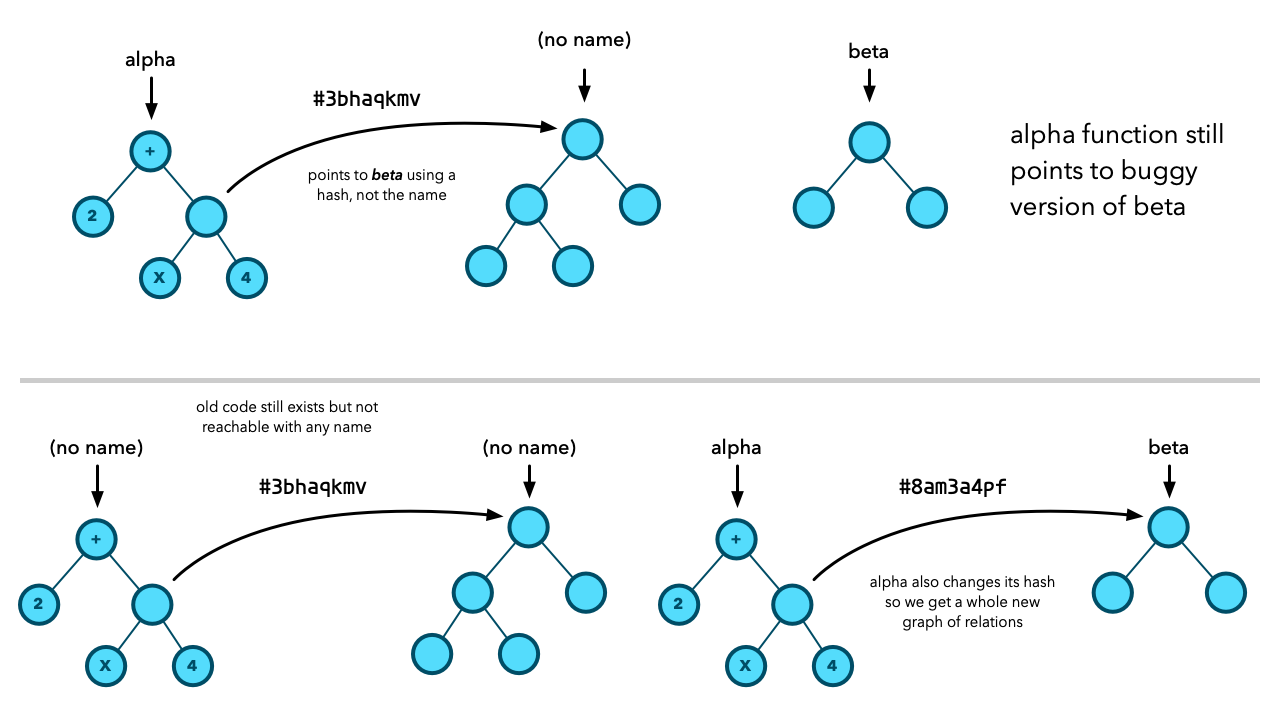

Say the alpha function and a number of other function point to beta, and it turns out that there is a bug in beta. I modify the code of beta to fix the bug. But that will produce a new function with a new hash!

In my example, beta has the hash #3bhaqkmv, but this new betafunction will have an entirely different hash, which means alpha and everybody else are still pointing to the old buggy version of beta!

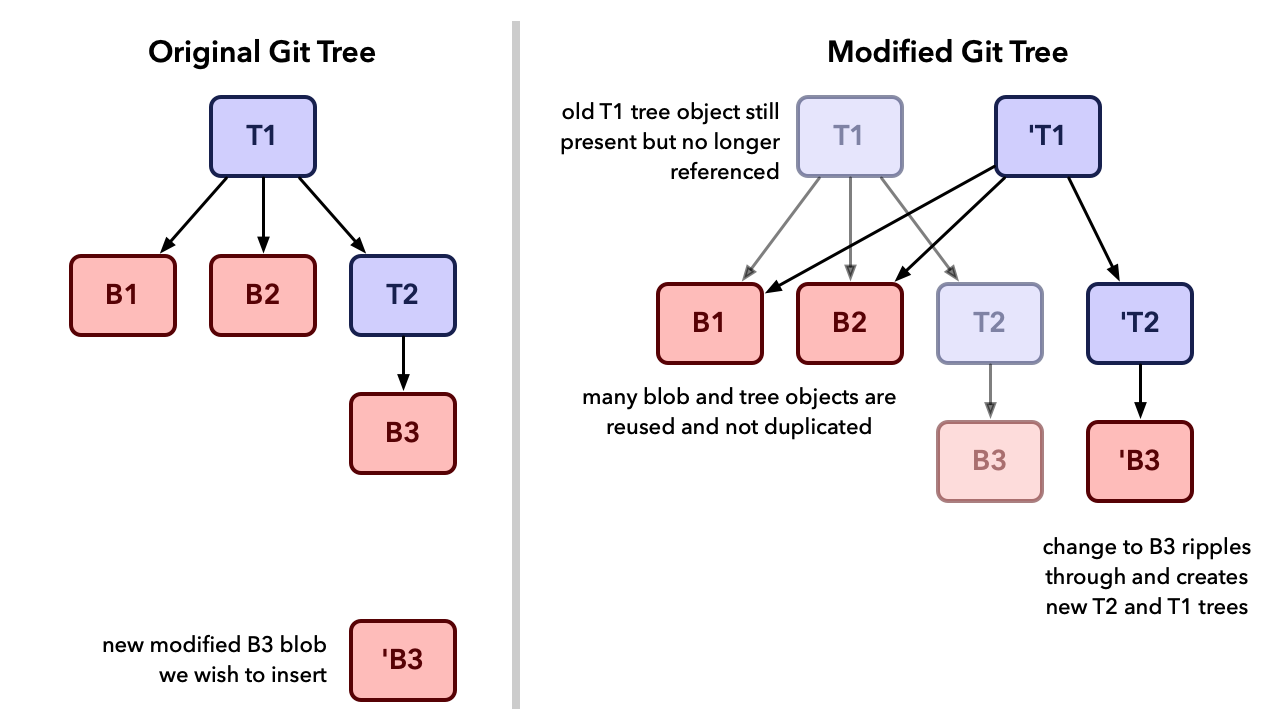

I have seen many commenters reading about Unison make this remark, and it is frankly a bit surprising given that exactly the same issue would exist in Git. If you change a file in Git and commit it, you get a blob object with a new hash. The old tree object will however still keep pointing to the old blob. Git solves this problem by duplicating the old hierarchy with new hashes.

The illustration above illustrates this effects with blob objects named B1, B2, and B3. Tree objects are named T1 and T2. The changes the code in a file foo.cpp which was previously stored in blob B3. When committing the change to Git, we get a new blob 'B3 representing the modified foo.cpp. Since the hash of T2 is derived from hashing all its content including reference to B3, we get a new version of T2 which we call 'T2. Because it gets a new hash, T1 will also need a new variant T1 to point to 'T2. All this happens because every object in the Git database is immutable. You only ever add objects. You don't change them.

However, we get new commits which point to these new duplicate structures, and that is what we work with. It may seem space wasting, but as demonstrated by the illustration above, there will always be a significant amount of object reuse between the old and the new tree structure.

Unison works in a very similar fashion, although I don't know the details quite as well as I know Git. Changing the source code for a function will produce a new AST with a new unique hash. That change will bubble up the call hierarchies. Every function that calls beta will get a new duplicate variant, which will get a new unique hash. The function names alpha and beta will be updated to point to these new ASTs. The old ASTs will remain, but may not have any names pointing to them.

What About Source Code on Remote Computers?

This bubble up effect fixes code locally, but what about duplicates of the same code on remote machines? Easy, each change creates a patch object which describes the code change. This patch object can be distributed to other computers and allow developers to apply the same change to their code.

What if the Function Signature Is Changed?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Erik Explores to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.